'Top Gun' to 'Queen's Gambit': IP Laws and How Not to Break Them

As lawsuits fly over rights, 'The Briefing' pod's lawyer-hosts talk Superman, LeBron's tattoos and Jerry West

A few months ago, I discovered The Briefing, a podcast about IP from Scott Hervey and Josh Escovedo, two lawyers at Weintraub Tobin. Since then, it has shot to the top of my playlist. Short of going back to law school, this is one of the best ways to deepen your understanding of copyright, trademark and IP law. if you’re interested in this stuff, I highly recommend it as a must-listen.

The pair had both been giving talks and blogging about IP law for more than a decade, but when the pandemic hit, they searched for a new way to reach people and hit on the idea of a podcast. The Briefing recently celebrated its 100th episode.

They've done shows on everything from whether Top Gun: Maverick infringes on the copyright of the article that inspired the original film, whether Inventing Anna defames one of its characters, whether Toy Story 4's Duke Caboom violated Evel Knievel's IP and whether movie cars merit copyright protection, including the Batmobile (yes) and Eleanor from Gone in 60 Seconds (no).

All fascinating and informative. I love it. Every episode makes me feel a little smarter and a little more informed.

Another thing I appreciate about The Briefing is that the episodes are crisp and efficient — most are in the 7-10 minute range.

I reached out to Scott and Josh to tell them how much I liked what they were doing with the podcast and got a chance to ask them a few questions about IP law. Here are highlights of our conversation:

Optionist: I’ve always been curious about the utility of securing life rights, which isn’t necessarily something that is legally tangible.

Scott Hervey: As far as real people as characters, in the U.S., public figures are generally considered free game from a right of publicity standpoint. If they're dead, it's even better for writers, because dead people don't have life rights. Although some states have posthumous right-of-publicity rights, but generally they contain a carve-out for creative uses for characters that are based on historical figures. I have been on either side of my share of life rights deals. One side is they provide you with access to information that might not otherwise be publicly available — personal documents, photographs, et cetera — that the public doesn't have access to; stuff that might not be in an article, for example. If the person's alive, they'll sit down and talk with you and provide consultative services that you don't normally get. This was central to Olivia de Havilland's lawsuit against FX under the right of publicity statute. The court basically found that the producers’ First Amendment rights outweighed whatever right of publicity (de Havilland) may have under the statute in California. The court said film and television producers may enter into rights agreements with individuals for a variety of reasons; however, the First Amendment simply does not require such acquisition agreements. It's also done so you don't get sued. A lot of times, the life-rights payment will be less than your insurance deductible. Your insurance provider's gonna require it, or they'll exclude any claim relating to the life rights from coverage.

You guys did a great episode over the lawsuit around whether Top Gun: Maverick impinged on the copyright to the original article which served as the underlying rights to the first movie, but wasn’t credited (or compensated) on the sequel. The question was whether the sequel also drew on the original article.

Hervey: The original article in California magazine by Ehud Yonay was a work of non-fiction. Paramount acquired the rights. Did they need to acquire the rights? If all they were searching for were the facts, then maybe not. But there's a lot of creative elements that are in the article that make it into the movie. What's not protectable are facts. What is protectable is the manner in which the facts are portrayed. When court's parse, they'll look at the protectable elements and they'll separate out non-protectable elements from the work as a whole. They'll look at what's left to make a determination as to whether or not it is substantially similar.

“A lot of times, the life-rights payment will be less than your insurance deductible. Your insurance provider's gonna require it, or they'll exclude any claim relating to the life rights from coverage.”

I noticed a similar thing in the The Fast and The Furious sequel credits. The original movie was based on an article, but highly fictionalized. It credits the article. But the sequels, from the third or fourth on, stop crediting the article. I've always wondered why that happened. Why isn’t the original article always credited as source material?

Hervey: I'm not familiar with that case, but some of the time when you're dealing with derivative work sections in rights agreements these subsequent production provisions require that the subsequent production be based on the work, where work is defined as the material that was optioned.

Ahh, so the further away you get from the original, the more latitude you have? In F9: The Fast Saga, for instance, they go into space and that's clearly not in the original article.

Hervey: Right.

With everybody online, is the definition of who is a public figure becoming more expansive? There are more people than ever before who are marginally famous. How is the definition of a public figure expanding?

Josh Escovedo: I suppose you could argue with the age of information, Instagram and TikTok the definition of a public figure has expanded immensely. Now, does that change how the law defines who is or isn't a public figure? Probably not. The definition is still the same, but then we have to look at that law and apply it to the world that we live in and say, who is a public figure? When Freddie Freeman, the first baseman for the Atlanta Braves, came to the Dodgers (in 2022), there was this instance when all of a sudden, he sends out this notice to the Players' Association that says, "I'm firing my agent.” Then months later, a journalist published an article addressing this issue, saying Freeman was never presented with an offer from the Braves; his agent basically broke the rules of being an agent by failing to present that offer. Well, his agent at the time, Casey Close — who is a huge MLB agent — filed suit, as did his agency, Excel, for defamation. When that happened, I found myself, as somebody who does media law, asking, is Casey Close a public figure for purposes of defamation analysis? I thought I would say, yes. He would definitely be a limited-purpose public figure. I think that's just kind of a way to think about whether it is expanding. I think when you really break it down into this limited-purpose public figure analysis, you'll find that a lot of these individuals who are big names in their respective industries are also at the very least limited-purpose public figures.

[Ed. note: Close sued the reporter, Fox Sports’ Doug Gottlieb, who recanted the allegation, closing the matter for Close.]

Former Lakers coach Jerry West threatened to sue for defamation over the way he was portrayed in HBO’s Winning Time. Did that controversy have a chilling effect on people who want to adapt stories involving the living?

Hervey: We did an interesting deep dive into that particular issue. He didn't end up suing. When you're doing a television show about a real person, you do need to tread carefully because public figure or not, they still have a claim for defamation. I think what should make everybody's antenna pop up is the Queen's Gambit lawsuit, because that was one where Netflix did not succeed on their early motion to dismiss. This was all based on a throwaway line in the last episode, but the court found it to convey a defamatory import about the real Russian chess star.

(Ed note: In the final episode, Beth Harmon, played by Anya Taylor-Joy, defeats a male competitor at a tournament in Moscow. An announcer explains, “The only unusual thing about her, really, is her sex. And even that’s not unique in Russia. There’s Nona Gaprindashvili, but she’s the female world champion and has never faced men.” Gaprindashvili sued, saying that the claim was inaccurate — she had faced more than 50 men by 1968 when the episode was set — and was “grossly sexist and belittling” and defamatory. Netflix ended up settling with Gaprindashvili for undisclosed terms.)

Are these problems creatives encounter more often with secondary or tertiary characters?

Hervey: You still have to watch out for defamation, right? The Inventing Anna case involved a main character. The way that you get around these tertiary and secondary characters is composite characters. Stay away from using real names. If you're gonna defame somebody, make them up. Don't make them a real person.

“I think what should make everybody's antenna pop up is the Queen's Gambit lawsuit, because that was one where Netflix did not succeed on their early motion to dismiss. This was all based on a throwaway line in the last episode.”

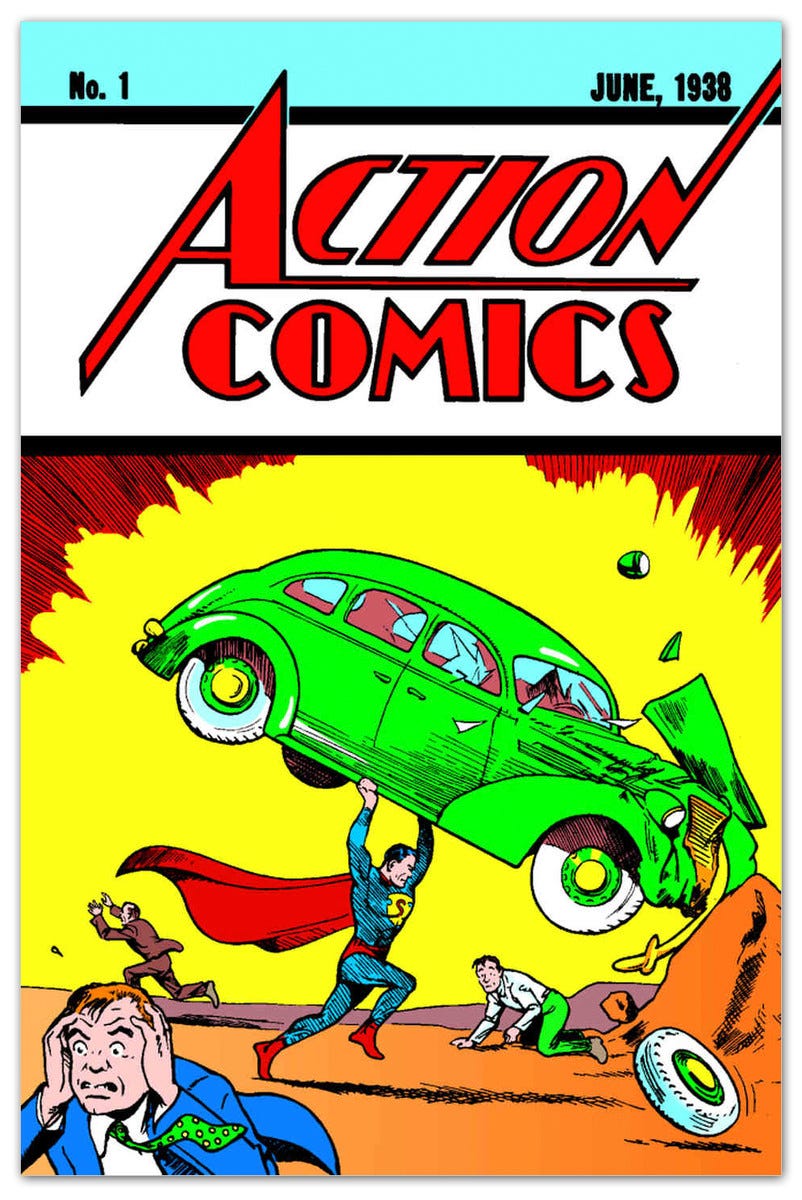

With so many big characters entering the public domain, I'm trying to understand the distinction between copyright and trademark and how that's going to play out with these well-known characters like Winnie the Pooh, which I just wrote about, Buck Rogers or The Hardy Boys. We're going to get Superman in a decade. How does this work in the law?

Escovedo: The distinction between the trademark and copyright law are such that trademark is intended to be a mark that creates some sort of a designation of origin. In other words, anytime you see the word Pepsi, you think of Pepsi products. That can be in words; it can be a logo. It can be words plus a logo. It can even be in the form of trade dress, which is essentially the packaging that you've come to associate with a particular product.

In the case of Superman, the trademark might be something like, “It's a bird. It's a plane. It's Superman.” As opposed to how Superman's costume looks in his first appearance. I imagine when Superman enters the public domain in 2033 there’ll be enterprising creators.

Hervey: They'll never be able to use any of the Superman trademarks to sell products, goods or services. That'll never happen. They may be able to make movies or write books or television shows or whatnot. The title will be problematic because there's an issue in trademark law where the title of single creative works can't serve as a trademark; however, if you have a serial — a series of books like The Hardy Boys — you can trademark the title for entertainment services. That trademark loops forever, as long as I continue to renew it. So there's a broad, broad spectrum of protection that you get in trademark rights that are not related to the protection and copyright.

Escovedo: What about the Playboy Enterprises versus (Terri) Welles case?

Hervey: Yeah, she referred to herself as Playmate of the Year (ed note: to promote herself on her website).

Escovedo: Exactly. So she listed herself as a Playboy Playmate of the Year for 1981. Playboy said, nope, not under our watch. And they filed suit against her.

Though she had, in fact, been the 1981 Playmate of the Year.

Escovedo: They found that ultimately, she wasn't using the mark to designate any sort of goods or services. She was simply saying, I was once a Playmate of the Year for this company.

Hervey: That's why she ended up winning that particular case.

Escovedo: An issue involving Great Gatsby, which came into the public domain last year, I think helps illuminate this issue a bit more. I immediately saw on Amazon that an author was going to be selling a work known as Nick, which is the sequel to Gatsby from his perspective. Now, what he's done there, he is not using the word Gatsby in his title. So, he is not utilizing what is potentially a trademark, although I don't know if that's been registered or not as we sit here at this moment, but he is picking up this idea that was expressed in a tangible medium, and he's running with it and taking the story of Nick Carraway further.

Imagine you're talking to an author or a creator. What advice do you give to somebody who wants to acquire their IP, besides get a good lawyer?

Hervey: (Laughing) To be honest, really that's it. One thing to think about: Is this the right partner for me? Everybody's always excited to get a deal, but ask, "Who are they? Do they have the capability to actually make this into something or is it just somebody who is equally new to the industry?” If you're the writer and this is your one thing, are you gonna entrust it to that person? So one, pick your partner and two, pick your lawyer, because your lawyer and/or your agent are going to be the ones that drive the economics and deal points. Don't pick your cousin who practices real-estate law — get a proper entertainment attorney.

Are there big cases that we might see in front of the Supreme Court this year that we should be watching?

Escovedo: Generally speaking, I don't find the political alignment of the court to be dispositive of any intellectual property questions. Obviously, you have some more business favorable decisions on the right than the left at times, but that doesn't always shine through in these decisions. With that said, there are two very significant cases before the Supreme Court this term. One of those is the Andy Warhol Foundation dispute over the recreation of the photograph of Prince. (Ed note: Warhol used a photograph by someone else as the basis for his portrait of the singer. The photographer claims the use violated her copyright.) The Warhol Foundation says, "That's a Warhol." The district court said, it’s transformative. The Second Circuit turned around and said, that's not transformative. Scott and I think the Second Circuit was at odds with one of its own decisions. It's really interesting because the Supreme Court hasn't addressed fair use in the context of artistic expression since 1994. It’s been a long time coming and this is just an issue that really needs clarity.

And the other case?

In the trademark context, we have the Jack Daniels vs. VIP products case, which is a dispute where VIP products created a spoof dog toy known as the Bad Spaniels Silly Squeaker dog toy. It's a parody on the well-known Jack Daniels bottle that says “Bad Spaniels” instead of “Jack Daniels.” Jack Daniels doesn't see the humor in the situation. VIP had a First Amendment defense that it's a parody protected as artistic expression. The district court agreed, the Ninth Circuit agreed. And now we're going to see if the Supreme Court also agrees. That has serious implications because the world wants to know what you can and can't do juxtaposed to someone's trademark rights in creating some sort of artistic spinoff. The argument that was raised by the INTA, which is the renowned International Trademark Association, is that this particular dog toy does not constitute a traditional medium of expression. They want to draw a distinction between, for example, a dog toy or a shoe, versus music art on a canvas or something of that sort.

Hervey: That effect is what's known as the Rogers Test, which is something that is relied upon quite frequently in the production of any type of entertainment content.

Escovedo: The Rogers Test has two prongs. The first prong is whether it constitutes artistic expression, or if it has value as artistic expression. Essentially, there's case law that basically says — and this is slightly paraphrasing — that the work does not need to rise to the level of Anna Karenina. The second prong is, is the particular use expressly misleading? The argument that was raised by INTA is that this particular dog toy does not constitute a traditional medium of expression. They want to draw a distinction between, for example, a dog toy or a shoe, versus music art on a canvas or something of that sort. And so we'll see how the court ultimately deals with this.

This makes me think of a line of cases you’ve talked about on the pod about lawsuits that involve the tattoos of real people featured in video games.

Hervey: So we kind of had resolution on this. First, we had the Mike Tyson case that was about his face tattoo, which scared everybody to death, and then we had Solid Oak Sketches (a tattoo shop) which dealt with the tattoos on LeBron James and other NBA players depicted in NBA2K. There, the court said the use of the tattoos were de minimis (a legal term to indicate something trivial to the claim). Even if it wasn't de minimis, the court found an implied license — players had an implied license to use the tattoos as elements of their likeness, and the defendants had the right to use the tattoos in depicting the players in the video games. That was 2016.

Then in 2020, Alexander versus Take Two Interactive came around, which is about WWE2K and Randy Orton that had to do with his tattoos. The reason why this one's a little bit different is, according to the testimony of the tattoo artist, she basically said, I always told Orton, no, you can't use my tattoos. You can use my tattoos as you appear on TV, but you can't use them in merchandising. The court found all of this to go to the fact that there was no implied license, and the court found that the works were not de minimus. Now we have an issue with talent showing up with their real tattoos. Production requires waivers, or the tattoos have to be covered.

What is the biggest blind spot people have about IP?

Hervey: That's an easy one: How complex it all really is. When you're talking about rights, there's nothing straightforward or easy about it.

The interview was lightly edited for clarity and concision. We’ll be back again on Friday with my weekly optionable IP picks, for paid subscribers only.