Brian Grazer Q&A: How the Wash Post Deal Happened

Imagine's co-founder, now intertwined with the venerable paper, reveals what's coming

Imagine exploring series around last days in Afghanistan; Mexican law enforcement

WaPo publisher Fred Ryan, Bryan Lourd, played key roles in deal

No more Watergate stories: ‘Saturation point’

Welcome to the Optionist, a sibling subscription publication to The Ankler. Today we're featuring a conversation with Imagine Entertainment co-founder Brian Grazer about the company's new first look deal with The Washington Post (this interview is free to all readers). Just a reminder that our regular Friday picks of great optionable IP is now available only to paid subscribers. In the last couple issues, we've featured the story of the Navy's original female Top Gun pilots, a fun spin on Alice in Wonderland for kids, and an unsung January 6th hero's memoir, plus many others. If you haven't subscribed yet, you can do so here.

The supercharged pursuit of adaptable intellectual property in Hollywood has led to a frenzy for new material, particularly in regards to newspaper and magazine stories. Traditionally, most options for articles were one-off deals. But times have changed. With most newsroom profits challenged, publications see the marketplace of options and adaptations as a source of new revenue (often with an eye to mining older overlooked material) and a brand builder. Magazine and newspaper journalism also has proven to be a source of prestige content – The New York Times won five Emmys in 2020 and this year scored its first Oscar (for documentary short). In Hollywood, the explosion of peak TV has led to an IP scramble. News organizations have responded by establishing production companies (like Vox Media Studios and Vice Studios, for example) or by striking exclusive deals with partners in Hollywood.

So it caught my eye when The Washington Post announced a first look deal June 14 with Imagine Entertainment, brokered by CAA’s Bryan Lourd (whose agency represents both companies). The parameters of these deals are often opaque and it isn’t always clear to other creatives what material in the Post might still be available and what’s off limits. So I reached out to Grazer to ask about the deal, what kind of projects he had in mind and to offer general thoughts on adapting journalism for the screen.

The Washington Post/Imagine deal is a multi-year partnership that gives Imagine an exclusive first look to develop material, including all Post IP past, present and future. (Financial terms weren't disclosed.) Since Amazon founder and current executive chair Jeff Bezos also owns The Washington Post and Imagine has worked with Amazon in the past (it just scored six Emmy nominations for the Lucy and Desi doc that aired on Prime and the upcoming Ron Howard directed Thirteen Lives will debut on the streamer July 29), some may wonder if the deal includes an Amazon Studios component or distribution on Prime. It doesn’t. The Post first look deal is agnostic when it comes to distribution partners.

Over the course of our Zoom (conducted just before the July 4th holiday), Grazer talked about how the deal came about, will work (Imagine is open to lots of partnerships), and what projects he’s looking at (the last days of U.S. involvement in Afghanistan is one). Here are highlights from our conversation (lightly edited for clarity and concision).

Tell me how this came about. What made you interested in the Washington Post?

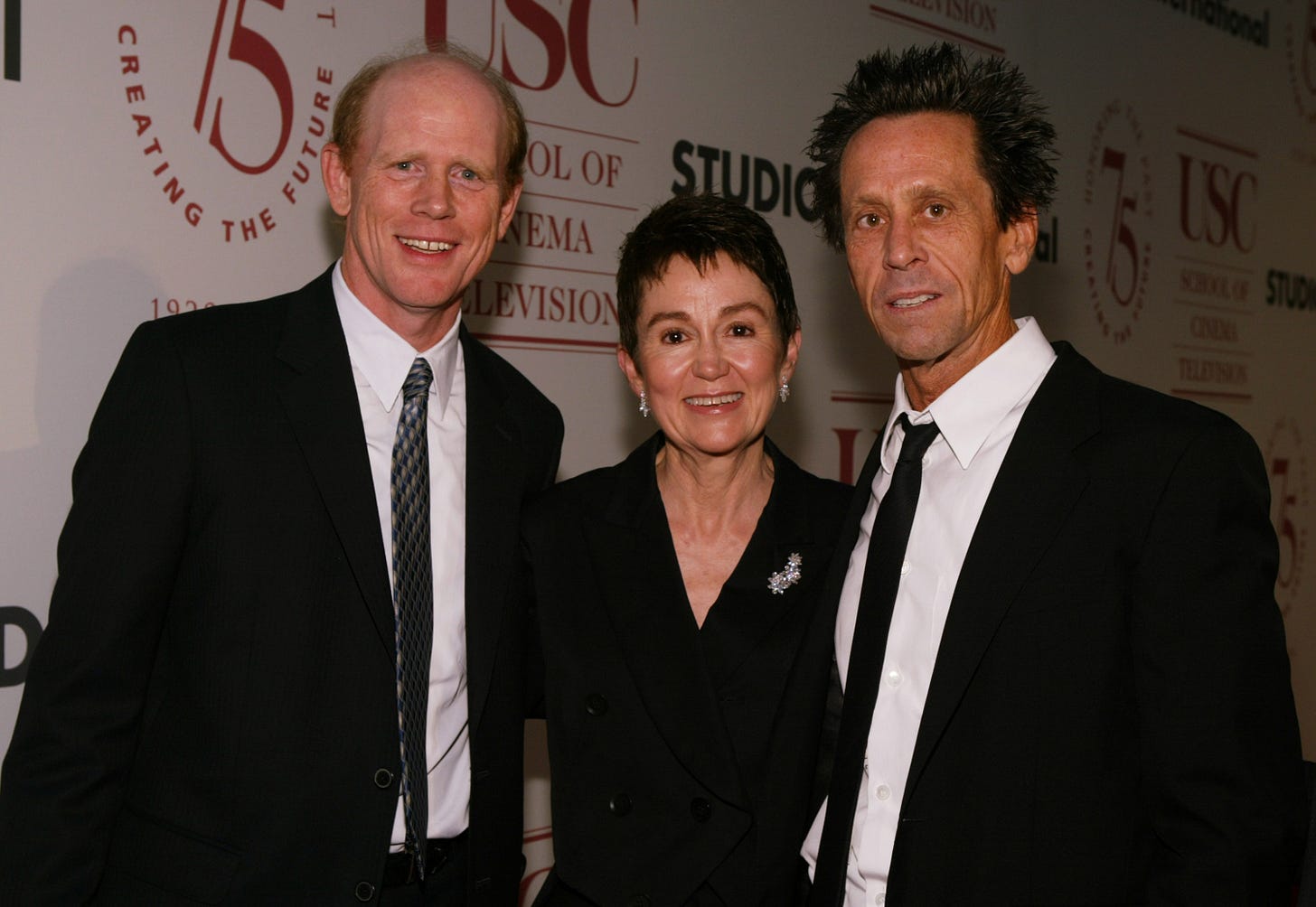

Grazer I'm on the board of USC film school — have been for, I think, 16 years. Elizabeth Daley [the dean of the film school] had a phone call from Fred Ryan, who is the Post's publisher, with questions about who were the good producers, who were the good agents, who were the good possibilities for a partnership with the Washington Post. She asked my advice on that question. And, you know I didn't even suggest us initially. I just gave her a sense of the landscape. And then she put me together with Fred Ryan.

What made you want to do it?

There are few publications in the world that are [as] preeminent as the Washington Post. It's in that top category of esteemed publications that uncovers and breaks stories that are provocative, arresting and truthful and have been of great interest, including, of course, the Watergate story which became All the President's Men. I had a zoom with Fred Ryan and a follow-up meeting. I was just very excited about the possibility of getting under the hood of the Post and understanding what writers are writing. I thought it would be amazing opportunity for Imagine to have a first opportunity on all the the pieces that have been written, or are going to be written.

How's that going to function? Do you have a window for a certain amount of time? There's probably more material at the Post than you could develop.

There's much more material. It's creating a mechanism for a partnership so we've created a team. Justin Wilkes, Imagine’s chief strategy officer, is leading the partnership on behalf of Imagine. Tony Hernandez, Lilly Burns who head up scripted content along with all of our division heads, Karen Lunder (film), Kristen Zolner (TV), Sara Bernstein (docs), Stephanie Sperber (kids & family), along with our partner companies, Alex Gibney’s Jigsaw and Jax Media. I'm a participant on the team along with Ron Howard. We do a meeting every two weeks with many of the people at the Post. We get an intimate sense of which stories are being thought of. Of course we don't get access to every story right away. You can't have that because the writers have to have the privacy that they need or want until they decide otherwise. But it creates an intellectual collaboration of ideas and human beings. It causes all of us to be thinking about this. CAA, of course, is a big part of this. Bryan Lourd assigned many people to work on it, including himself.

Would you partner with others if there's a project you wouldn't want to develop?

If we passed on it, it would be sold by CAA separately. But even the things that we choose to do an option on, we would quickly partner with other people, whether it be a writer, director, producer, star, because we just want the best outcome. We just want the best content. We would welcome it and solicit it.

Can you just tell me about some of the things that you've already thought about?

I don't want to be too specific.

Sure. I understand.

We want to do something that involves the final days of Afghanistan and we have something there. We also have a project that involves Mexican law enforcement agencies. We also have other projects that examine systems. We have a project that involves, I don't even want to say which sector, but athletics. Violations or cults within [the] world of athletics.

There’ve been a lot of movies ripped from the headlines. There was The Post, another Watergate movie. Spotlight, the Boston Globe-based movie about sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. I'm wondering if any of those projects influenced how you're thinking.

It doesn't. I mean everything influences everything else. I don't see that I'm going to be chasing stories that reexamine The Post's expertise on specific cases. I already made a movie 25 years ago called The Paper. As far as we're concerned, if somebody else might want to do that or if there's a great story that emerges out of The Post that interests us, I probably [would] look for a partner.

You’re doing Thirteen Lives, about the young Thai soccer team lost in a cave.

We do a lot of true stories. We've done Thirteen Lives, Apollo, 13, Friday Night Lights and A Beautiful Mind — many things like that. The Beatles documentary, which is great. Lots of documentaries that are true stories — Carlos Santana, Julia Child. I can go through them all.

With Thirteen Lives there wasn't a story underneath it that was optioned, right?

I don't want to say you're right, but I don't want to say you're wrong. I don't think we did option a story.

The reason I ask is, would you have approached Thirteen Lives differently after this deal, in terms of using the Post's resources?

I don't think we would've approached it differently because Ron had a very special way he wanted to look at it. You know, he wanted to see everybody's perspective in this incident. I think his vision was pretty focused and clear about what he wanted to do so I don't think we would've done that, but there are stories. If I want to do something that involves the United States military, I would look for a partnership with the Post first, before I went out to agencies or writers. I think I would go with our ideas first to them, in fact, in some cases.

The New York Times has led the way among newspapers in doing this. To the extent you paid attention to that, are there things you want to emulate?

We've worked with The New York Times before and successfully. I think in a collaboration, citing the one we have now with the Post, you learn as you go. I might ask the Post, which I'm going to, about something to do with the United States military. I'd state what I want, what I'm trying to achieve. And then working that backwards, I'd say, do you have a story that would help achieve that sort of cinematic outcome? Is that too esoteric?

No, that's exactly right, because one of the things the deal offers is access to the expertise of the Washington Post. It's a conversation, right? Whereas if you don't have this deal, you're just waiting for a story to come.

Yeah, so it's not about just being more proactive. Alex Gibney is also part of the Imagine group. We might have the feeling from the collection of information out in the environment that there's corruption, that there's an extreme amount of corruption in a certain sector. And then we would say to the Post, ‘this is interesting to us. Do you have a story that's true that sort of fits inside of this possibility?’

We've gotten so much Watergate stuff with the 50th anniversary. There's Gaslit, The Post, All The President's Men. Do you think that there's more in the Post archives to mine from Watergate?

I've reached sort of a saturation point on it. One person might say, ‘no, I want to do a Watergate story' or a story that is about the lawyer's perspective on Watergate. Our team at Imagine might say, ‘well, that could be interesting, but not for us.’

The magazine business is, as you know, in trouble, which has hampered longform magazine writing as underlying material. Does that make newspapers more important?

It probably makes it more important for having the rich IP.

Do the troubles of the magazine business affect the kind of material you see in any way? Does that make sense?

Does it make sense if you're saying if the magazine industry is less of a resource now? Yeah. And particularly to make longform journalism. I think audio is so important now. So I think that's, I think the way to channel longform content. Anything that can be made into audio seems to be fresh, exciting content.

What ways do you want an author involved in an adaptation, either nonfiction or fiction? Do you want an author to write a screenplay? What’s your general view on it?

It's so specific to the author, but I think if an author is really dedicated and passionate and has a particularly exciting vision about what he or she would do, then I usually give them the chance to write it. I'd say, write an outline. I would give them the same opportunity I would give a screenwriter.

Some people think there's a downside — authors are too close to the material.

I don't think of that. It's more, do they understand the form of a screenplay? The form itself is so specific to creating cinematic images and building central and secondary narratives that live inside a focused narrative. It's that I probably have more concern about, not based on objectivity of the subject, but more just the mastery of the art form itself.

One of the other things that has come up lately in dealing with nonfiction material is how important is it to get the subject on board.

I always want the subject on board. Yes. I don't really want to be at war. I want people to be feeling good about the representation of themselves or the subject. Sometimes you miss. You start off and everyone involved in the subject is on board and then they just don't like the process or they second guess, but the ship has sort of sailed. You try to be versatile, you know, so that everyone can feel like they’re a part of this.

I was thinking about this because with Winning Time, Lakers legend Jerry West was unhappy with how he was portrayed. I'm not asking you to specifically critique that, but it just raised these questions.

Oh, God, I don’t how to answer that question. Look, you often can't make everybody happy. As long as your intention is pure and you're trying to do that, that's kind of all you can do. I liked Winning Time. I thought that was so much fun, but I understand the question.

Maybe the Winning Time team underestimated the platform Jerry West would have to critique it versus, say, an Adam Neumann (WeCrashed) or Elizabeth Holmes (The Dropout), who maybe aren’t going to speak out.

Yeah, it varies on the project for sure. You're not always making movies or television shows about people that are heroic or that are in fact doing noble things.

How do you balance storytelling with fidelity to the facts? You're making a movie, so inevitably you have to deviate from facts a little bit to make a story.

Even in Apollo 13. The character of Gene Kranz played by Ed Harris really existed and the majority of mission control was under his watch, but we also had to fold in some other characters that did a few things during the mission. Right? So we made it a composite character. A lot of it is the spirit in which you're doing it, because it's impossible to get it all right.